The "blackwashing" of the fine art world

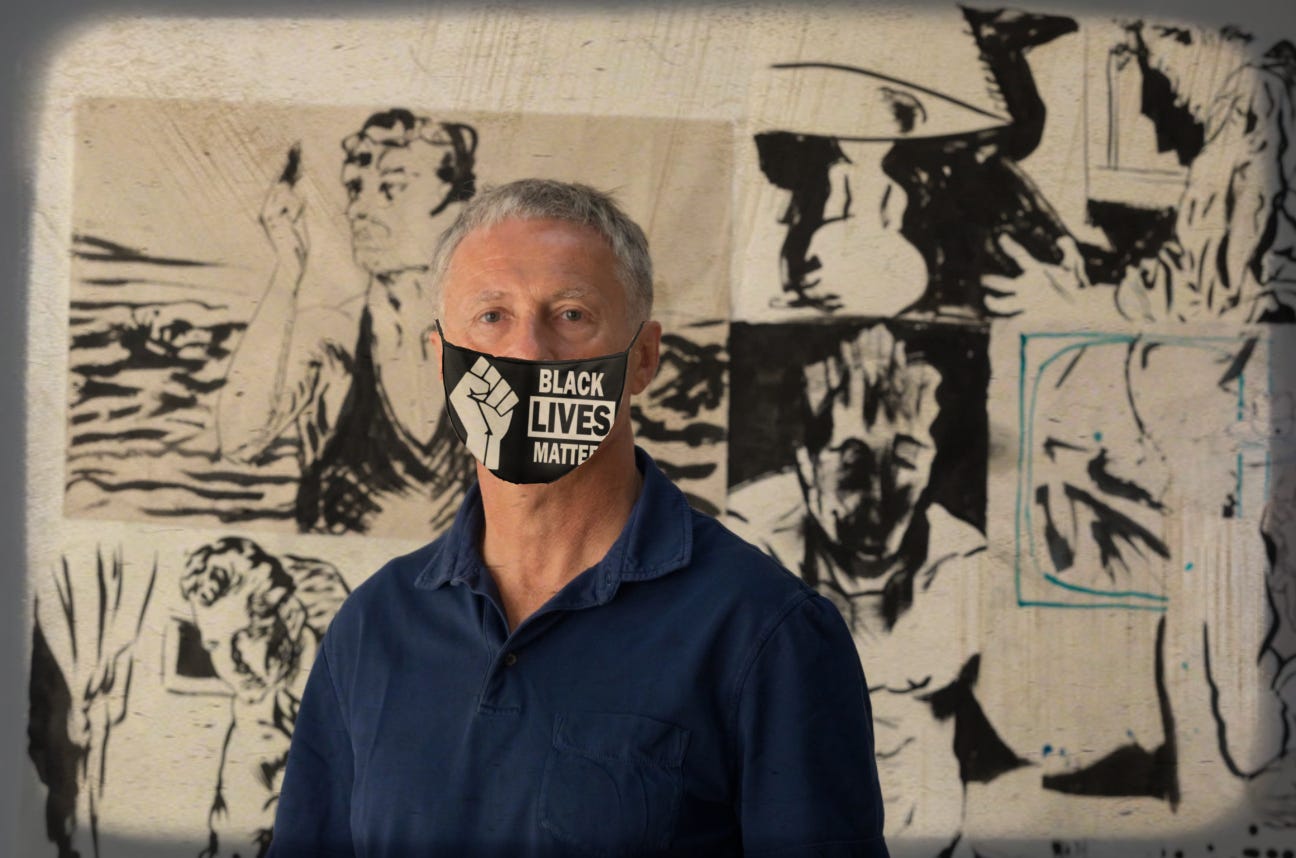

What does it mean when the world’s second-richest art dealer, David Zwirner, lends his capital and influence to the creation of an “all-black” art gallery?

David Zwirner recently hired black gallerist Ebony L. Harris to run a new “all-black” commercial gallery in Manhattan. Major strides have been made towards getting black artists more attention, Zwirner told the New York Times, but art world employment remains stunningly white.

Shouldn’t we then celebrate this announcement as what social justice for marginalized people looks like? Isn’t the world’s second-richest art dealer simply empowering Harris, and thus, empowering black people in the art world and beyond?

On one hand, it’s a good thing that there are more black artists and curators in the art world.

But consider the idea that Zwirner is deftly using yet another Black Lives Matter moment to maximize brand visibility and operate his global capitalist venture beneath a media-constructed veneer of social justice and racial equality. More broadly, the “all black Zwirner” space is connected to a troubling trend: the culture industries enforcing racial essentialism and neoliberal reductionism.

Blackwashing is the term Cedrick Johnson has used to call the process of corporations signaling towards racial equality without acknowledging their own roles in exploitation.

“These forms of anti-racism are simply about firms trying to expand their market share through expressions of care and concern,” he writes. Blackwashing can be applied to the SJW-friendly marketing strategies of big global contemporary art galleries and Zwirner’s “all-black” art space is, without question, the apotheosis of art world blackwashing.

This is peak “radical chic.”

David Zwirner is, according to Forbes, second only to Larry Gagosian as the most financially successful dealer in the art world. He’s the bourgeois German art-dealing son of a bourgeois German art-dealing father who sells hundreds of millions of dollars of art to the likes of Nicolas Berggruen. He’s the billionaire investor whose think-tank Berggruen Institute is an ideological guiding force for 21st-century neoliberalism. Among other clients who profit off of the exploitation of ordinary working people: American industrialist and convicted tax evader Peter Brant, Israeli heir, and Trump fundraiser Tico Mugrabi.

This isn’t surprising. Art makes up the largest unregulated market of goods in the entire world, and oligarchs use it to launder money. We should never accept any premise that states that the art world is a vector of justice.

That makes David Zwirner Gallery both a luxury goods sales operation and a money-laundering service. The creation of an “all-black” art gallery is a “good deed” that works to obscures its position in the global marketplace. But the problem goes deeper. Critics, like Adolph Reed, Jr., have pointed out that “anti-racism” is to capitalism what racism was decades ago, in that it sows division amongst the underclasses along cultural lines and directs their rage away from the means of production (and their bosses) and towards one another.

Contemporary corporate “anti-racism” prophets, including Ibram Kendi, Robin DiAngelo, and Ta-Nahesi Coates, have cleverly created a binary from which one can choose to be “anti-racist” or “racist.” To be truly anti-racist you must buy their books. You must eat from the trash-can of their ideology. If you don’t, you’re a filthy white supremacist. And it’s worked. Anti-racism, absent class analysis, is a booming business. Donors have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into Black Lives Matter causes in the months since the George Floyd protests, which have resulted in questions about where all that money goes. Corporations have followed suit. Every streaming site has a “black lives” section on its homepage and #BLM merch is red hot.

Zwirner, ever the pioneer, is making a canny market calculation by cynically co-opting racial justice. He would see the financial upside in hiring Haynes to run his “all-black” gallery, realizing that he can tap into the white guilt of collectors who will be happy to buy art by black artists and can then feel like they’ve done something morally good that still benefits them financially. A win-win. Let’s call it “white guilt-free consumerism.”

Given it was only some decades ago that Jim Crow was brutally enforcing laws that demanded black people stay in their “all black” schools and their “all black” hotels, what’s also disturbing is the silence from allegedly radical artists and writers endorsing “woke segregation.” Juliana Huxtable, Sara Cwynar, Ajay Kurian, and other contemporary artists all offered positive text and emoji combinations celebrating the announcement on Haynes’ Instagram. Why hasn’t there been one bit of criticism aimed at a “separate but equal” art gallery?

Probably because artists, and as in academia and activism, are part of the precariat and identity is waged as a weapon of upwards mobility in the art world. As we know from Rachel Dolezal and, more recently, Jessica Krug, claiming a “marginalized” identity can absolutely give you an edge in a competitive bourgeois marketplace. An anonymous curator friend of mine told me in private that a major art fair denied his application, citing his submitted artist’s “whiteness” and “maleness,” as its submission reviewers’ reasoning.

Consider the letter written by artist Hannah Black that demanded Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till be removed from the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Black is a woman of color, but also an elite educated member of the petit-bourgeois from the United Kingdom. What she was accusing Schutz of – that the white artist was cynically profiting off of a black political issue and an image of “ black pain” – could equally be leveled her way. Despite growing up comfortably, she claims to experience a miasma of blackness that she somehow feels on a metaphysical level. She postulates that “blackness” is a “cultural identity” that all black people can tap into, regardless of class position.

As Walter Benn Michaels noted in his response to Hannah Black’s letter, “The opposition to cultural appropriation is a claim to cultural capital. They represent a variation on a similar theme, the demand for racial justice as a demand for equality of access to elite institutions.”

Black and other artists need us to see them as oppressed, because that oppression is their claim to cultural capital, and their continued success is then interpreted as a resistance to oppression. That explains then why these art world figures of color, like Ebony L. Haynes, get to market being hired by Zwirner to direct an “all-black” art gallery as being manifest progress for the entire population of black Americans.

There’s a symbiosis at play. An “all-black” gallery gives artists of color space where competition is significantly smaller and gives them a direct pipeline to Zwirner’s exclusive clientele. Zwirner gets celebrated as an actor for justice, while Haynes and the artists who will show at this space will be rewarded with financial and cultural capital.

In the end, it’s cynical careerism masked as political progressivism.

This is definitely a topic worth exploring more in depth. The problem is of course in focusing so much on the very top of the art world, which will almost always present a skewed POV from which to critique the whole of the art world, which is not as unified as one might think. For example, the art world has a terrible track record when it comes to aiding and abetting in gentrification of neighborhoods, but it is also a fetishized subject within the art world that gets hotly debated every time it comes up and the art world tends to flagellate and self-critique itself with as much zeal as it does now over race and representation. Zwirner and Gagosian are only a small handful of art dealers who have massively benefited from covid and the subsequent BLM protests turned branded intellectual property. The top of the art world is awash in money right now, but the middle and the bottom are either struggling or entirely shut down, many for good. 70% of San Francisco artists have left town and there's an ill conceived UBI proposal on the table that would give a lucky 130 artists $1000/month to live in the most expensive city in the US. That's just for perspective. How will these artists be chosen? Merit? Class? Race? Religious affiliation? What is termed 'blackwashing' is simply another, most likely toothless, criticism of the way that the art world does business at the very top. Clement Greenberg was already making connections between the art world and money in the 1930s and that's what it comes down to in the end. I have numerous articles and essays floating around related to the art world and its (dis)contents. Right now what we're seeing is a coming wave of Robin D'angelo style racism awareness HR training coming down the pike at every major and minor university and art museum. So in essence it will be figures like Zwirner and Gagosian that will be used as the guiding light behind all the 'good' that is happening within the art world. We're truly in an upside down world.

https://www.tompazderka.substack.com/