The antiracist left’s approach to history is anti-historical

Works like "The 1619 Project" ultimately use the past as a tool to save capitalism from itself.

“Finding out what time it is doesn't require learning the inner mechanics and history of the timepiece. And, as a practical matter, engaging those more remote issues risks detour into debate on the history and mechanics of watch-making that distracts from the task of ascertaining the time.”

— Adolph Reed, Jr.

“Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways. The point is to change it,” Karl Marx concluded in the famous final line of his Theses on Feuerbach.

Walter Benn Michaels, English professor and literary theorist, says this axiom is due for an update:

“The bourgeoisie have tried to understand history,” Michaels quipped in a recent interview. “The point, however, is to forget it.”

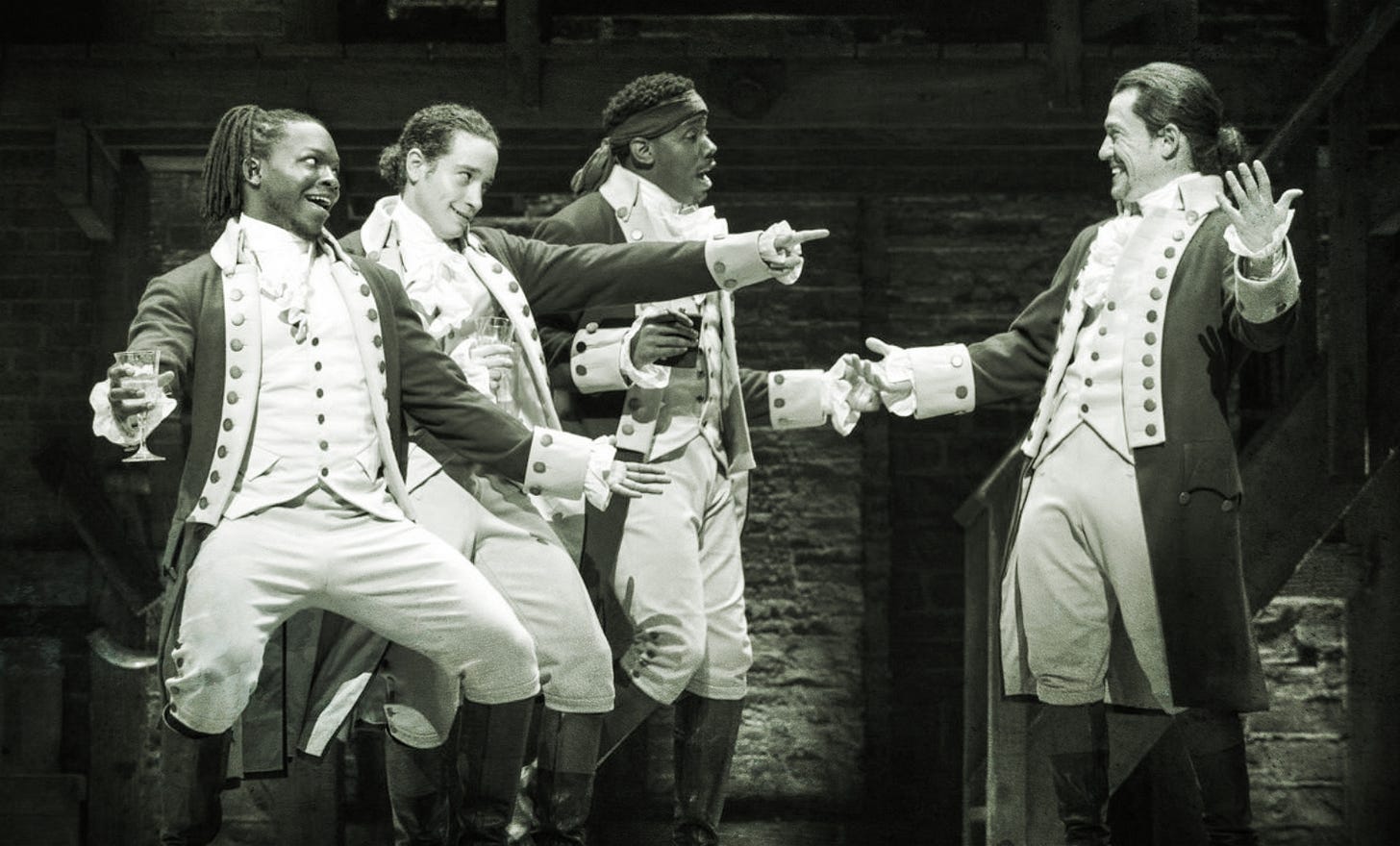

A new wave of liberal anti-racists, whose works currently dominate sales charts, reading lists, academic settings, and even the cinema, take the opposite approach. Although some differences exist among them, most theorize current racial injustices with references to those of the past, from “The New Jim Crow” to the New York Times’ 1619 Project. These liberals, whose arguments have been adopted by some on the Left, not only posit an unbroken chain of racism from the days of chattel slavery to today but also invoke the strategies and tactics of historic social justice movements as models for present-day organizing.

These analogies ultimately hurt prospects for a movement capable of battling both economic and racial inequality. Alluding to past victories as inspiration means grafting historically specific circumstances onto the present without regard to whether such comparisons are strategically appropriate. It also leads to blindly copying strategies and tactics honed during the fight against institutions—e.g., chattel slavery or the Jim Crow South—that either no longer exist or no longer wield their former influence.

Sinners in the hands of an angry media

Such arguments ultimately reflect the alienation of upper-class anti-racist creatives from the material reality of working-class people of any race. Their theory-by-analogy fails for one simple reason: Race is a historical construct, and the way it has operated throughout American history has depended on the status of economic relations in each epoch.

The liberal failure to understand this is exemplified by the New York Times’ 1619 Project, a series of essays, podcasts, and curricula by journalists and academics, all of whom claim the U.S. was built on an autonomous, anti-black racism rooted in seventeenth-century chattel slavery.

The Project’s authors claim this racism is responsible for a uniquely brutal form of capitalism, one predicated on the exploitation of “black bodies” (disturbingly enough, the Project’s authors seem to have forgotten the wholesale extermination of Native Americans). In an essay on the U.S. economic system, 1619 Project writer and Harvard sociologist Matthew Desmond decries American capitalism as evil not because capitalism itself is inherently exploitative, but because U.S. capitalism specifically was built on the backs of slaves. The problem is not capitalism but racist capitalism.

Racist ideas, we’re taught, are a transhistorical force. Racism, as described by the Project’s founder, Nikole Hannah-Jones, is America’s “original sin.” Blacks are said to suffer from the exact same strain of racism as under chattel slavery or Jim Crow. Exaggerated as it sounds, this argument forms the bedrock of Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th, which argues that because the 13th Amendment allows prisoners to be used as unpaid labor, slavery never actually ended. Similarly, law professor Michelle Alexander proposed that blacks in the United States suffer under a “New Jim Crow” regime under the post-1968 prison industrial complex.

Desmond, Hannah-Jones, DuVernay, and Alexandra all define anti-blackness as a pathology, a mind disease inherent to “white DNA,” passed down over the past four centuries that ceaselessly inflicts rhetorical and physical violence against black bodies. Under this framework, racism serves as a fetish for whites as opposed to an ideology used to prop up social inequality.

But as law professor James Forman, Jr. argued in a critique of Alexander’s thesis, “the Jim Crow analogy promotes a reductive account of mass incarceration’s complex history in which, as Alexander puts it, ‘proponents of racial hierarchy found they could install a new racial caste system.’”

Along the same lines, historian Patrick Rael wrote, “If we can only see ongoing racial oppression as a remnant of slavery, then we can’t see it as a problem of our own age. And if we can’t understand mass incarceration as a problem of our own age, we can’t critique the mechanisms that foster racial and economic inequality in a system that is supposed to be blind to both.”

Capitalist supremacy

It’s telling that the most successful working-class struggles for equality—including the Populists, the labor battles of the 1930s, and today’s efforts by service workers for better wages and benefits—are rarely cited by those in the leftist vanguard fighting for racial inequality. These movements understood that to be anti-racist, one first had to be anti-capitalist which, by virtue of their class positions, academic racialist hucksters will simply never be.

Over forty years ago, historian Judith Stein criticized some of her colleagues for reflexively proffering ‘racism’ to explain why blacks hadn’t yet achieved racial equality.

“The explanation is advanced before the investigation is conducted,” Stein noted. “Racism is reified, divorced from the concrete and complex experiences of social groups in particular circumstances...By reifying and isolating race consciousness and racism, [the structures of power in society] are ignored....and we are led to believe that men make history according to their racial likes and dislikes.”

A decade later, historian Barbara J. Fields pushed back on this racism-explains-everything lens of history. She took a critical eye at historians who “think of slavery in the United States as primarily a system of race relations—as though the chief business of slavery were the production of white supremacy rather than the production of cotton, sugar, rice, and tobacco.”

Similarly, Jim Crow laws were designed to keep black and white farmers from rallying behind the Populist movement as well as secure a supply of cheap, expendable labor. They were not—as argued by liberal anti-racists like Alexander—mechanisms of enforcing “whiteness.” Nor were they designed solely to keep blacks at the bottom of the social hierarchy. The same goes for the Thirteenth Amendment’s exemption on penal labor, which was initially intended as an alternative to capital punishment.

Southern planters, of course, took advantage of this by passing Black Codes, explicitly racist laws which forced many newly freed slaves into conditions reminiscent of, and sometimes worse than, their former plantations. While these laws were undoubtedly discriminatory, their real purpose was to secure cheap labor for planters, which the planter class used to undercut interracial workers’ and farmers’ alliances.

The approach taken by liberal anti-racists is not just ahistorical but antihistorical, heightening the illusion that the main issue facing blacks, even today, is racism, not capitalism. Class differences among and between blacks and whites are erased in favor of a Manichean black-white racial binary dressed up in Victorian race science.

By contrast, research by economist Dionissi Aliprantis reveals that the real driver of today’s racial inequality is the growing income gap between the rich and the poor writ large. Aliprantis found that had the median income gap between black and whites closed in 1962; median black family wealth would have been ninety percent of median white family wealth by 2007. The most direct route to combating racial inequality in the present is economic redistribution that strikes at the core of capitalism.

This fact doesn’t mean we should turn a blind eye to anti-discrimination legislation, which has increased civil rights for women, people of color, and LGBTQ people. Still, any antiracism movement which refuses to attack capitalist exploitation amounts to a variant of the same recipe that made our current neoliberal stew.

If the Left truly seeks a more egalitarian world—and not merely a more proportionally diverse cast of pols and capitalists—we have to build a universal working-class political movement capable of strong-arming the institutions that reproduce economic and racial inequality today.

Your argument against the tendency amongst liberals and some leftists to think of racism and racial categories as unchanging in their meanings throughout history is spot on.

My question is - as per Michael’s quip - should we really move away from an investigation into the historical interplay between racism and capitalism in this country, just because many liberals have done a shoddy job with the recounting? Surely what differentiates the left from liberal thought is, in part, our focus on how class power is concentrated and promulgated through social institutions. And these social institutions have a history that needs interrogation.

A good piece. Insightful academics thinkers who take into account class issues and the capitalist economy are unfairly maligned