History or Hate?

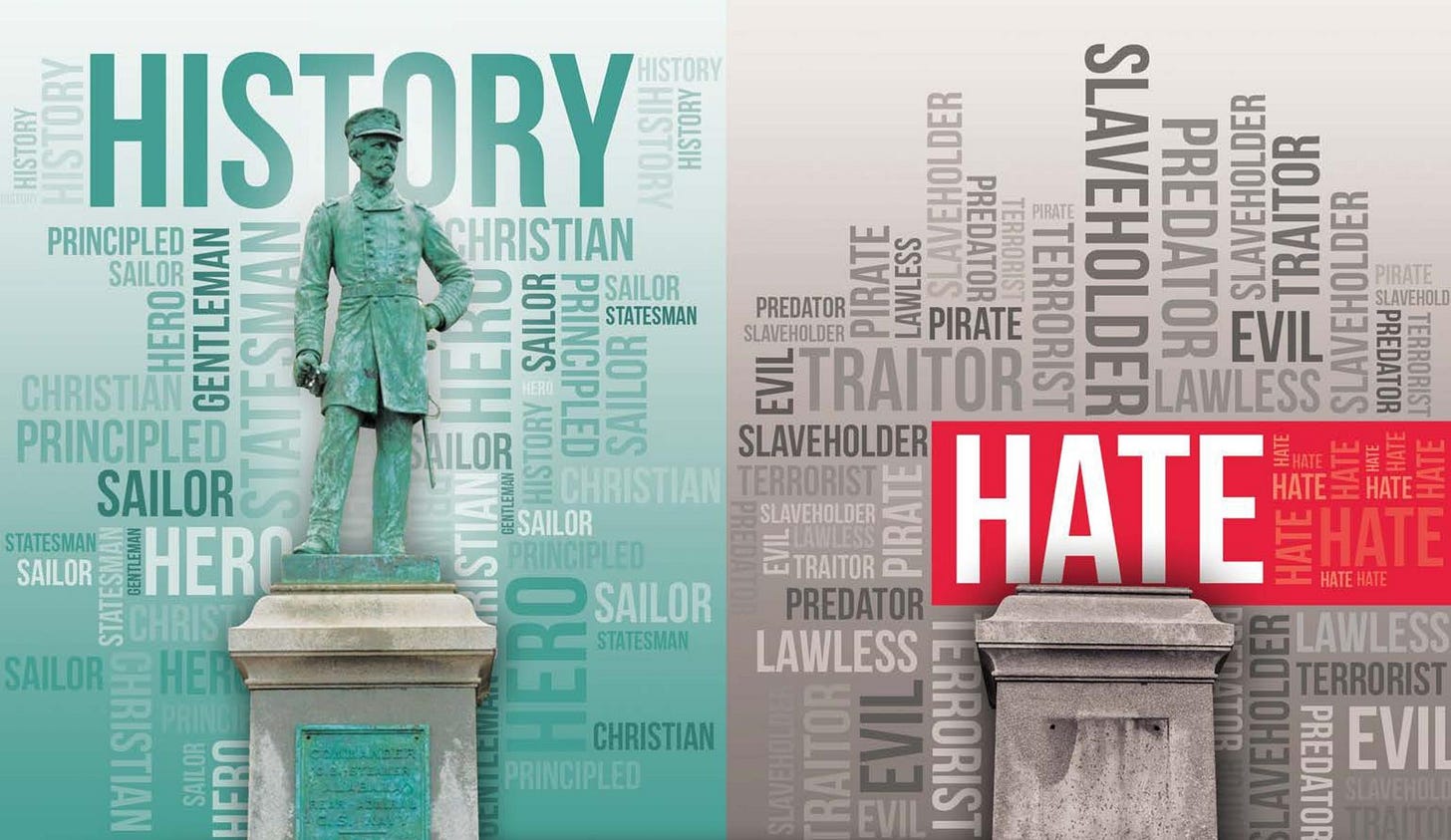

The future of a 120-year-old monument to a Confederate admiral—and the broader fight over Southern history—remains unsettled.

Anderson Humphreys’ life changed forever the first time he caught sight of his great-great-great-uncle immortalized in statue form. On a family road trip to Gulf Shores decades ago, his mother pointed out Mobile, Alabama’s monument to Confederate Admiral Raphael Semmes and noted the familial connection.

“I remember looking at it in awe right before we drove through the Bankhead Tunnel,” the Memphis advertising executive recalls of his boyhood self.

An initial fascination with the Semmes bloodline and Civil War history became an obsession in college in the ‘60s. That’s when Humphreys began conducting countless hours of research and interviews to map out his family tree. “It was an exercise in insanity,” he admits.

The insanity never really ended. In 1989, Humphreys published Semmes America, an exhaustive 736-page account of all of his genealogy work. Twenty years later, Humphreys tried to convince Hardeman County, Tennessee, to erect nearly 10,000 3D-printed statues of Civil War soldiers as part of a ghostly-looking tourist spot marking the little-known Battle of Davis Bridge. He even named his firstborn daughter in honor of the Confederate admiral (“Semmes is a good name,” he says).

Naturally, the Semmes scribe quickly noticed when Raphael’s bronze replica was unceremoniously yanked from its pedestal in downtown Mobile. He broke the news to an email group of far-flung relatives he maintained:

“Semmes America,” Humphreys wrote. “Alabama city removes Confederate statue without warning. History is under siege once again. Sad day.”

That message set off a fierce debate among the 70-or-so Semmes descendants, with battle lines mainly drawn along old north-and-south borders and between generations. Those living in the south and born before the Civil Rights movement were more likely to lament the mothballing of the statue.

“He was a brilliant, self-educated man who was renowned throughout the world for his accomplishments, not the least of which was to be the cause of the first of Geneva conventions,” wrote one senior male relative. “His compassion is well established in his treatment of prisoners, respect for life, dealings with some mutinous sailors. Nothing good has ever been accomplished by hiding truth.”

Younger and northern-based members tended to disagree.

“Statues are not history,” read one dissenting email. “It is time to come to grips with our national past, and as a country to not celebrate slavery and those who supported it.”

It’s a microcosm of the broader fight over symbols and identity that continues to rage in communities in Alabama and much of the rest of the south. In May, the death of George Floyd set off a flurry of nationwide Black Lives Matter and racial justice protests, acts of vandalism, and government actions that have led to the removal of over 130 Confederate monuments and memorials.

More may be coming down soon. Days before Christmas, Robert E. Lee's statue was lifted off its long-time perch at the US Capitol’s National Statuary Hall in Washington D.C. as part of a provision in the National Defense Authorization Act passed last month. President Donald Trump vetoed the bill because of his opposition to the legislation that establishes a commission to study changing the names of bases named for Confederate military leaders. But Congress overrode the veto last week.

In tiny Albertville, Alabama, a group of protesters continues to show up twice a month to oppose Confederate iconography displayed at the Marshall County Courthouse. At their most recent demonstration in December, they placed fake slave body bags on the courthouse lawn to evoke the slaves owned by John Marshall, the former U.S. Chief Justice who the county is named after.

The Semmes statue was one of the first Confederate monuments to fall last summer, but the matter hasn’t been settled in Mobile yet either. For the past six months, the Confederate admiral’s eight-foot-likeness remains quietly tucked away in the bowels of a History Museum of Mobile storeroom. There are vague plans to return to the public eye, but director Meg Fowler says the museum isn’t ready to talk about how or when.

“We’re actively working through the process and consulting members of the community about it,” she said.

Meanwhile, the life of Raphael Semmes—the flesh-and-blood human being—has been obscured by the passage of time and the symbolic weight of the rebel battle flag he once hoisted above his ship.

What can history tell us?

Captain Raphael Semmes was a Confederate naval officer, but not the kind you might expect.

No, he never uttered the famous phrase, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" in the Battle of Mobile Bay during the last days of the Civil War. That’s a common mistake—even among Mobilians—that credits the wrong man and wrong army (See: Union admiral David G. Farragut).

Nor did Semmes fight much. As captain of the CSS Sumter and CSS Alabama, he engaged with a Union warship only twice between the summer of 1862 and the spring of 1864—winning once. His official job was commerce raider, tasked with hunting and looting American merchant vessels in waters sometimes as far away as South Africa or remote islands in the Indian Ocean.

It was a role that Semmes had invented for himself.

“The Confederate Navy as a whole had almost no resources: It doesn’t have sailors, it doesn’t have shipyards,” says John Beeler, a history professor at the University of Alabama. “So Semmes had convinced (Confederate secretary of the Navy) Steven Mallory that he should be hunting northern merchant vessels to destroy Union commerce.”

The plan was a brilliant one. By the end of Semmes’ campaign, he’d captured 65 trading vessels, burning 52 of them. In all, the South’s premiere seawolf cost the North upwards of $6 million—roughly $100 billion in today’s dollars.

“He ended up driving the Union navy crazy,” added Beeler.

Surprisingly, he managed to do so bloodlessly. The vast majority of his rendezvous with American ships looked more like glorified traffic stops than raids. The shots his crews fired upon merchants were blanks, designed to scare them into surrender. He took prisoners for safekeeping only to drop them off at neutral ports. These facts are evidence cited in his defense.

“He was an intelligent, thoughtful man who wasn’t taking lives, and quite the opposite, was a gentleman in many ways,” says Anne Semmes, a Connecticut writer and Semmes descendant.

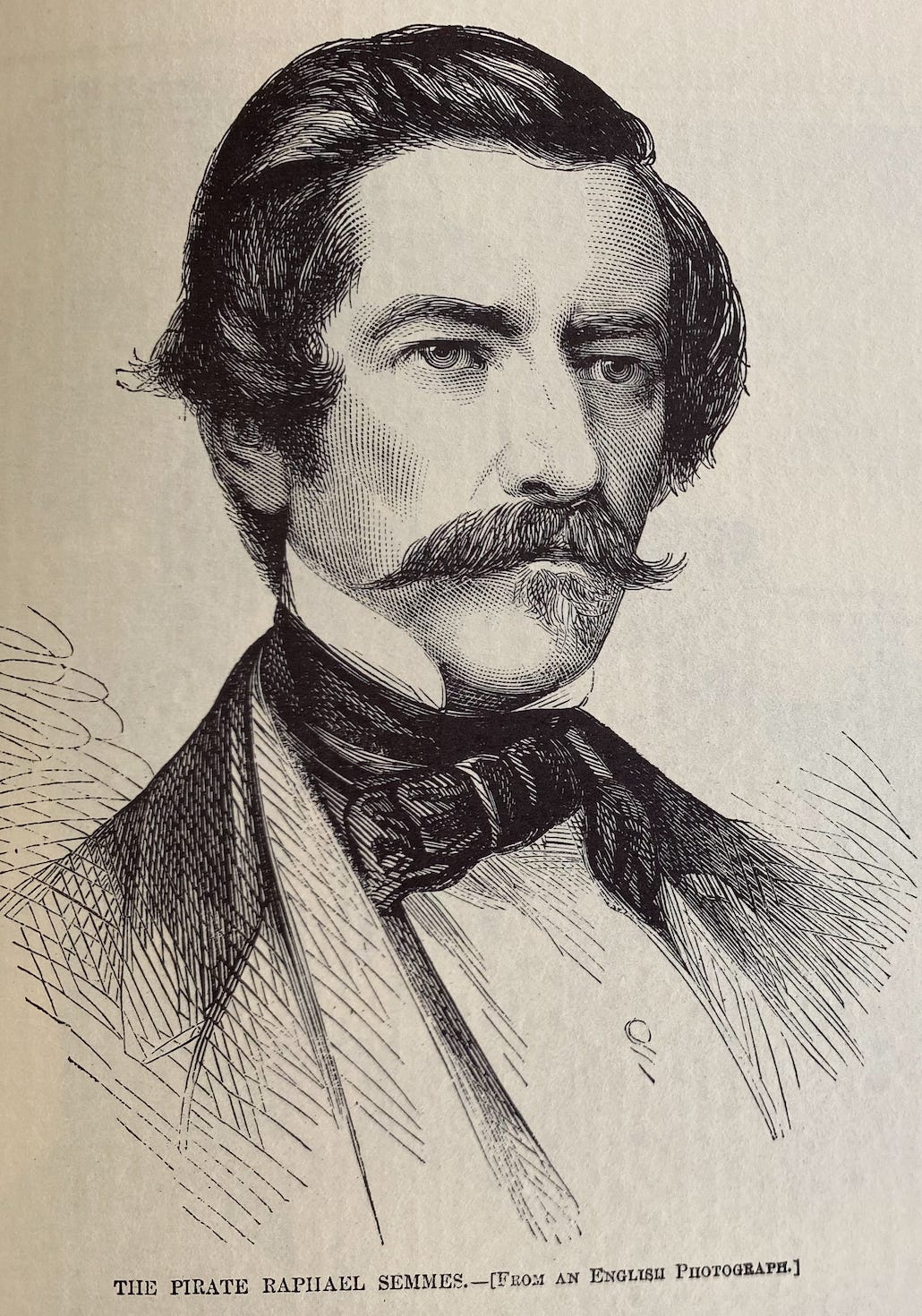

In the North and international press, he developed the opposite reputation, a lawless pirate and traitor who preyed on the defenseless—the south’s answer to Bluebeard or Captain Kidd.

“For some months, he made the civilized world ring with the fame of his exploits over unarmed merchantmen which he robbed and burned,” noted the January 3, 1863 edition of the New York-based magazine Harper’s Weekly.

Semmes’ evil deeds were exaggerated in the north, as was his swashbuckling hero persona in the south. But the Union was closer to the truth, says Beeler.

“He plays nice up to a point, and the fact that he makes sure passengers and crew are safe somewhat mitigates that negative depiction. But in the end, what he’s doing is piracy, and so he’s still a pirate,” he adds. “In fact, I’d say today we’d consider him a terrorist.”

A pirate’s life isn't for everyone. Day-to-day life aboard the Alabama looked little like a Pirates of the Caribbean movie. It consisted mostly of eating spoiled food, sitting in foreign ports waiting for supplies, diplomatic wrangling, and long stretches of tedium punctuated by short encounters with random boats.

By the late spring of 1863, matters had gotten worse for the man known as Old Beeswax—a reference to the bushy, well-manicured mustache that framed his slender face. The Alabama had grown leaky, and its motley crew became mutinous to the point that his officers wore pistols and ordered to shoot anyone who attempted to desert. Multiple years at sea had also taken their toll on the 55-year-old captain, and he sounded ready to dock permanently.

“These three years of anxiety, vigilance, exposure, and excitement have made me an old man, and sapped my health,” Semmes wrote in his diary.

To top it off, his last major prize was literally full of shit. The Alabama’s officers had come aboard an unarmed merchant ship named the Rockingham, which was carrying guano. The vessel’s sailors tried to convince the Confederate captain that the excretable cargo—valuable as a crop fertilizer—was the Peruvian government’s property. But no legitimate documents could be found saying so, and Semmes decided that it was fair game because the ship had flown the Union flag. He ordered his crew to burn it all.

Conditions deteriorated to the point that Semmes was ready to fight the Union navy’s USS Kearsarge when confronted in Cherbourg, France in June of 1863—despite the Alabama’s disadvantages against an actual warship.

“Miserably fed, hunted, eluding, preying, destroying, is this a life that brave men would willingly have be continuous?” his published memoirs later asked.

On June 19, the outgunned and rickety Alabama fell victim to the cannons of the Kearsarge. A “fiery rain of shells” struck the Alabama during the hour and 10-minute long battle, and it began to sink; a spectacular scene later dramatized in a painting by French impressionist Manet. The fall of Semmes’ cruiser was also mourned by “Roll Alabama Roll,” a sea shanty whose lyrics influenced the University of Alabama’s fight song decades later with “Roll Tide Roll.”

More than half of the Alabama’s officers and crew were killed or captured in the skirmish, but Semmes managed to escape via a British yacht. His military luck seemed to end there. Confederate president Jefferson Davis promoted him to Rear Admiral—and later Brigadier General—after returning to the Confederacy in early 1865. By then, the War of the States was drawing to a close. His service ended with a whimper; he accompanied Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina during his surrender on April 26, 1865.

Union officers originally paroled him but, weeks later, arrested and jailed him for treason, piracy, and the ill-treatment of prisoners. Those charges were ruled unfounded and he was set free three months later without being brought for trial. He was released for political reasons, says Beeler.

“It would have been easy to try him as a traitor; Semmes took an oath and had a commission from the U.S. and then took up arms against the country he had a commission from. But if you want to reunite the country and you start killing traitors, it’s more difficult.”

Up until his death by food poisoning in 1877, Semmes remained unrepentant about the righteousness of his and the Confederacy’s role on the world’s stage.

A specific kind of revisionist history flourished in the defeated South almost immediately after the war. The so-called “The Lost Cause”—which originated from the title of an 1866 book by the Virginian author Edward A. Pollard—posited that secession, not slavery, was the driving cause of the Civil War. Rebel states had seceded to protect their rights, their homes and to throw off the shackles of a tyrannical government.

Southern writers and thinkers began to modify and even recreate the origin and meaning of the conflict and romanticize Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee as saintly martyrs who were the natural heirs to the Second American Revolution.

One such writer was Semmes himself.

“He was one of the more vehement of the Lost Cause mythology defenders,” says Beeler.

In the late 1860s, he disavowed his own wartime logs and private papers, which had been published by a London company, as a “meagre and barren record.” He penned a new autobiography between brief stints as a professor at Louisiana State Seminary and as editor of the Memphis Daily Bulletin.

The book, Memoirs of Service Afloat, often contradicted the content of his own diaries. In his prior writings, Semmes recounts a conversation with a colonial official about why he resigned from the U.S. Navy’s Lighthouse Board in 1861 and tendered his services to the government forming in the South. “I explained the true issue of the war—to wit, an abolition crusade against our slave-property; our population, resources, victories..”

He also warns a Brazilian that the Union is “...destroying our slave property, in their wild fanaticism and increasing madness.”

A few short years later, Semmes argued that slavery was a smokescreen.

“Great pains have been taken by the north to make it appear to the world that the war was a kind of moral and religious crusade against slavery,” Semmes begins in a chapter titled The Slavery Question. “Such was not the case.”

Certainly, Semmes was a man with a strict code. He displayed it frequently in his florid communications with colonial governors and genteel encounters with his aristocratic peers. If the Alabama inadvertently seized a ship from a neutral country, it was released from custody without harm. While looting a United States schooner in November 1862—for instance—he returned a prized telescope to its owner, the ship’s master, because it had been awarded to him for saving lives in South America.

But that magnanimity had its limits, especially when dealing with those in lower social classes. Because the Confederacy had no true navy, most of Alabama's 150 or so sailors were international mercenaries—mostly British—who swore their allegiance for the promise of loot and prize money for captured vessels. To Semmes, anyone below the officer class was suspect: “one hundred and ten of the most reckless from the groggeries of Liverpool,” he called them. He even jailed a man and put him in double leg irons for exclaiming “Damn them!” because he hated public profanity.

“The flinty Semmes was never an easy man to get along with,” noted a 1935 biography. “He was not one for conciliation or accommodating.”

He had a particularly fraught relationship with dark-skinned people.

While the Sumter docked at the French-held island of St. Pierre in 1861, Semmes was appalled by the lack of segregation between the races. ”The negro race is here, as everywhere else, an idle and thriftless one, and the purlieus of the town where they are congregated are dilapidated and squalid,” he wrote in his diary.

The feeling was mutual. One official noted that a group of free Blacks tried to sabotage Semmes’ boat on St. Pierre: “She was moored to a tree by a cable and so intense was the feeling of the negroes against her that a guard of ten marines and ten French soldiers was constantly kept to prevent them from cutting the cable,” read the report.

For Semmes, the subjugation of Black people was the natural order of the world.

A native of Maryland, he was the wealthy son of a tobacco farmer whose family owned slaves to work their plantation. By 17, his uncle—the Speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates—had pulled enough strings to get President John Quincy Adams to appoint him a midshipman in the U.S. Navy.

Semmes worked as a naval officer and lawyer—not a farmer—but he bought a plantation in Baldwin County on Perdido Bay in 1842 and owned several slaves when he moved his family to Mobile a few years later.

On a property deed filed in Mobile County on February 5, 1862, Raphael transferred a family of slaves to his wife, Anne, along with his furniture. He wrote: “To-wit, one negro woman named Matilda, a slave for life, two negro boys (some of the above named Matilda) one named Edward, and the other named Henry both also slaves for life.”

The inscription that adorned the 12-foot granite pedestal below Raphael Semmes’ soldierly statue read simply: “Sailor, Patriot, Statesman, Scholar and Christian Gentleman.”

Will the title of slaveholder ever be added to the list?

The statue’s ardent defenders downplay that aspect of his life. They argue that his prowess and honorable conduct in war were his defining features. And even if Semmes was racist, it’s a fool’s errand to hold people in the 1860s to today's moral standards.

That’s an argument advanced by David Toifel, a commander of the Mobile chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. “Lincoln, Grant, Sherman—by today's standards, they were racist too. Union heroes destroyed the American Indians. So, if using the criteria of racism, their statues should come down,” he said.

The SCV is in the business of preserving Confederate statues in the South. After all, the organization—which dates back to 1896—is the same one responsible for their construction and upkeep. They unveiled the Semmes statue at a widely attended public ceremony at Royal and Government Streets on January 7, 1900.

It’s no coincidence that it was raised during the implementation of Jim Crow laws, a patchwork quilt of state and local rules that maintained racial segregation through the ‘60s, says Timothy Lombardo, an assistant professor of history at the University of South Alabama.

“One of the ways that it was used to make Jim Crow a reality was the reification of Confederate generals,” says Lombardo. “It wasn’t hidden; they were quite explicitly monuments to white supremacy.”

That’s evolved and shifted over time. In 1966, Alabama governor George Wallace threw himself in a doorway to protest the University of Alabama’s first Black students’ enrollment. A half-century later, not many people, even Confederate-flag-waving Southern sympathizers, will argue that Semmes’ statue represents anti-black racism because race-based discrimination itself has lost favor over time.

“That’s an amazing trajectory since the statue was built 120 years,” says Lombardo.

A statue’s job isn’t to clarify or teach history—it often works as an ideological prism through which to see it.

“The monument debate often comes down to erasing history. But monuments erase history more than tearing them down does because you’re literally putting someone on a pedestal,” says Lombardo. “History is complex and messy, and casting anyone in stone, for good or ill, erases a lot of that messiness.”

Local activist D'Antjuan Miller admits that he knows little about Semmes’ life. But the statue’s uniform spoke volumes to him. As an African-American, he felt disgusted when walking past its prominent place above the Bankhead Tunnel in downtown Mobile and seeing the Confederate outfit.

“I knew Semmes was a Confederate admiral; he fought on the Union side and then joined the enemy. We don’t need to be glorifying that,” says Miller, who says he’s now running for city council in District 5. “To me, it’s about them establishing their territory. They’re symbols of oppression.”

So when Miller saw the news of Confederate statues being toppled by protestors or removed by city governments in Montgomery and Birmingham in the first week of June—he thought Mobile should be next. He was one of several who brainstormed the idea to organize a Black Lives Matter march on June 6 to demand Semmes’ removal. A flyer advertised the event as “Take Down the Monuments/BLM” and featured an image of a KKK hood over the statue with a rope pulling it down.

The march never went as planned. Under Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson’s orders, city workers vanished Semmes during the wee hours of June 5. “The values represented by this monument a century ago are not the values of Mobile in 2020,” says Stimpson. “I have no doubt that moving the statue from the display was the right thing to do for our community going forward.”

The mayor denies that it was in anticipation of the protest, though he did add that law enforcement had “tracked credible threats of violence ahead of its removal.”

The BLM group believes the city was trying to defuse the march. “I feel like we caused it, and it symbolizes a victory for anti-racism in Mobile,” says Travis Cummins, a graduate student at South Alabama and a march organizer.

On the other hand, the Sons of Confederate Veterans believe the Mobile mayor should still be charged with a crime for unilaterally removing the figurine in violation of the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act, which bars the removal of monuments over 40 years old. The city paid a $25,000 fine for breaking the three-year-old law.

“The people of Mobile are victims of a crime, perpetrated by the chief officer with the support of city council,” says Toifel. “To me, the city of Mobile giving in to a threat of violence, that's a hell of a way to run a city.”

Neither the march organizers nor Sons of Confederate Veterans were consulted about the Semmes statue removal, but Oliver Semmes was.

As the 92-year-old great-great-grandson of Raphael, he’s the closest living relative of the Confederate Admiral. He has also served as a kind of Grand Marshall of Raphael Semmes related-events of the past half-century.

“The mayor consulted me with what I think should be done with (the statue) and I felt for him,” says Oliver. “He had the risk of having a lot of damage done in Mobile, or he could yield. He didn’t do either; he took the statue down and put it in the museum for safekeeping. I think that’s a pretty good move.”

But, he says, he personally opposes the tearing down of statues.

“We’re too wrapped up in emotion and forgot there’s nothing wrong with the preservation of history,” he says.

Emotion seems to work both ways for descendants of Semmes. The Anderson Humphreys’ email sent to Semmes’ around the country led to a civil war of words about their distant relative’s legacy. The heated exchanges chafed Humphreys enough that he drew a kind of Mason-Dixon line in the mailing list.

Now there are two groups: one for those in favor of the public display of the statue and another for those okay with its removal. “It upset everyone and I’m trying to unite the family, not destroy it,” he says.

It’s proof that perhaps a house divided against itself about confederate memorials cannot stand.

(Originally published in the Lagniappe Weekly)