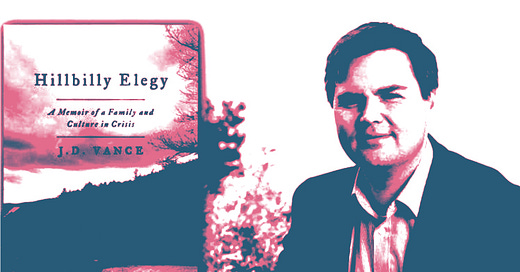

An anti-Hillbilly Elegy

Why the memoir I wrote for Jacobin isn't like the kind you'd read from J.D. Vance

“You should write your own version of Hillbilly Elegy.”

That’s what my uncle suggested when we talked last Christmas.

He’s a Hollywood movie producer who, like me, grew up in Springfield and spent a significant amount of his adult life in Chicago. He was once a radical leftist as a college student in an era when many were: the height of the New Left in the early 70s. He’s since slowly mellowed into something of a left-liberal now after many years living amongst the Hollywood elite in Los Angeles.

When we talked about politics during the primaries, he said he was a Warren supporter, arguing that Bernie was too single-minded about economics. I’d say he’s much more of a leftist than most in Hollywood, but to the right of Susan Sarandon (though he gets a ton of credit for producing a positive biopic on labor leader Cesar Chavez a few years ago).

What stands out most to me is his antagonism towards the white working class, something he has in common with countless other elite liberals. He used to fight with my dad about electoral politics literally to my father’s deathbed. I remember them arguing about Fox News and the efficacies of libertarianism as my father’s voice became faint because he was slipping away from liver cancer.

My uncle hates rednecks and Republicans and was glued to cable news during the Trump years with fears that the Trump-acalpyse was upon us. So, that always put a strain between his side of the family and ours, as he often perceived us as The Other, racist white trash making America a worse place.

“Us” is too broad of a generalization because I think he views me as a J.D. Vance-like character, someone who beat the odds and escaped the Hillbilly Hell of Central Illinois and joined the meritocracy. Thus, when I told him the latest chapter of my family saga, he suggested that I seriously consider writing my own J.D. Vance-like biography.

But what I tried to do in an essay that Jacobin Magazine published yesterday was to write an anti-Hillbilly Elegy, a piece that drew a dotted line between material conditions and institutional health in Illinois, which exacerbated my family’s poor quality of life.

That’s not to say I’m being purely deterministic and trying to cast my mom, grandmother, and nephew as victims of the state with no free will of their own. Believe me, I’ve argued with them about some of their decisions for decades, most recently about their position on COVID-19 vaccinations.

Yet, urban liberals too often agree with J.D. Vance’s conservative cultural assessment of the white working-class that understates the role that economic conditions, poverty, and crumbling institutions play in the everyday lives of those like my family. You have white privilege, right? Then you have no excuse not to pull yourself up by your bootstraps!

I understand where some of that myopia comes from because we’re all more sorted geographically these days. Many urban liberals can’t look out their window and see just how bleak life is in places that don’t have “Hate Has No Home Here” signs posted proudly in their front yards such as rural and midsized post-industrial towns that lack the saving grace of universities or aren’t located near the mountains or coasts. Many libs reside in successful city centers where the white working class has all but disappeared to the suburbs, exurbs, or rural areas. And so their sympathies lie—on paper at least—with their poorer urban neighbors, the Black and Latino workers who mostly dominate the service and caring industries in their neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, social media and omnipresent political media have built new psychic walls to add to the invisible walls of segregated neighborhoods by race and class.

Of the dozen or so messages responses I received to my essay, they fell into two camps. Either, ‘Wow, I really do live in a bubble because I didn’t know things had gotten so bad in a city like Springfield.” Or, readers told me their own personal tales of witnessing decline in some of the forgotten places in Illinois, places like Little Egypt in Southern Illinois or Pekin in the north-central region.

Stories like the one I wrote for Jacobin aren’t that uncommon, but as I have been reminded of in the past 24 hours, they’re just not usually told in the media.

Here’s the thing: Elegy is a term that means “a lament for the dead,” a song or poem of reflection that mourns a passing.

But the white working class isn’t dead, it’s just in precipitous decline. The rest of us can try to lend a helping hand to those in need, similar to the kind that the culture-at-large has vowed to do for underserved Black people in the wake of the George Floyd protests. The other option is to treat them closer to the way many of us have treated people of color in the past—lectures about personal responsibility, demonization, over-surveillance, mass incarceration, and ex-communication from polite society.

My prayer is that people like my uncle choose the former.

Well-done but sad piece on Springfield, IL circa 2021, weaved in with evocative family material. I wonder if things are any better today, three years later? The NYT series on assisted living institutions revealed that many people are facing similar nightmares as your grandmother.